From Michael Jordan to Luka Doncic, This Slovenian Star Connects ‘The Last Dance’ Bulls to Today’s NBA

Michael Jordan’s NBA career is replete with comeback stories, many of which have been recounted in The Last Dance.

Like when, during his second season with the Chicago Bulls, he recovered from a foot injury and led his team to the playoffs, despite severe restrictions on his playing time. And when, in 1993, he carried the Bulls back from a 2-0 series deficit against the New York Knicks to claim the Eastern Conference finals in six games en route to completing the franchise’s first three-peat. And also when, in March 1995, he left baseball behind to tip off another three-peat in the Windy City the following spring.

But there’s at least one comeback story you won’t see in ESPN’s docuseries that, while not exactly consequential to MJ’s legacy, is nonetheless illustrative of the competitive essence of His Airness.

From the very beginning of Chicago’s training camp in 1997, Boris Gorenc knew that—barring a major injury to one of the team’s wing players already under contract—he wouldn’t make the Bulls’ final roster. But if he couldn’t be one of the first Slovenians to secure an NBA roster spot, Boris wanted at least one thing from his time in camp: a matchup with Michael.

“I was bothering Michael every day to play one-on-one,” Boris tells CloseUp360 by phone from his home in the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana. “And actually, he always told me to get the fuck out of here after every practice.”

That is, until the final day of camp. Michael knew Boris wouldn’t be staying with the Bulls and would likely be heading back to Europe. So, at long last, he relented.

“He came to me and said, ‘Let's play,’” Boris says.

They would play to 11. It looked as though it wouldn’t take long to reach that mark—for Boris.

To this day, Boris isn’t quite sure whether Michael let him score the first few baskets on purpose. Nor can he explain how the next few found the bottom of the net.

“God help me,” he says, “it was crazy shots and everything went in.”

Boris had amassed what he thought was an insurmountable 9-2 lead on the GOAT. With the comfort and confidence of that advantage, he committed what has come to be known as the cardinal sin of competition against His Airness: he opened his mouth.

“I start talking shit against Michael,” Boris says. “Like, ‘Listen, I'm gonna tell everybody back home I kicked your ass and I'm better than you, and blah blah blah blah.’”

Next thing he knew, Boris was on the wrong end of an 11-9 loss. With that result cemented, Michael strutted (and Boris slunk) into a film session that head coach Phil Jackson had already begun.

“Everything stopped and, like, Michael was talking to everybody listening now, ‘I kicked his ass’ and blah blah blah,’” Boris says, “and I was acting like I'm mad. But, in fact, I was just so proud, man, just to have a chance to play with him.

“So for me, it was one of the things that I cannot forget.”

More than two decades later, with seemingly the whole world escaping into Michael’s past as refuge from the present day’s pandemic paralysis, Boris can reflect fondly on his footnote in a chapter of NBA history that’s more notorious than ever—and on a future he helped to forge for his home country’s on-court excellence.

Boris Gorenc (No. 3) appears briefly in Episode 1 of "The Last Dance." (ESPN Screenshot)

Nowadays, Slovenia is an important point on the basketball map. Despite sporting a population of just over two million people and a history of independence that doesn’t yet reach back 30 years, the Central European nation has become a hoops powerhouse, per capita and otherwise.

Six Slovenians played in the NBA during the 2006-07 season. Three—Beno Udrih, Rasho Nesterovic and Sasha Vujacic—have lifted the Larry O’Brien Trophy at least once. Two more—Goran Dragic and Luka Doncic—have been All-Stars. Three years ago, Goran and Luka headlined a Slovenian national team, which included Denver Nuggets rookie Vlatko Cancar and former NBA veteran Anthony Randolph (who holds a European Union passport), that went 9-0 to win the country’s first gold medal in the prestigious FIBA EuroBasket tournament.

But back in 1997, Slovenia was about as anonymous in the basketball world as its size would suggest. The country had gained its independence from Yugoslavia just six years prior.

Nonetheless, the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana was home to one of the most competitive basketball clubs in Europe: KK Olimpija. With a young Boris on the roster, the Dragons, as they are known, won the first eight Slovenian Basketball League titles and the first four Slovenian Cups. Despite lacking the big budgets and international talent of most EuroLeague clubs, Olimpija’s domestic success and development of local players helped it gain entry into the continent’s top competition, culminating in the 1994 FIBA European Cup championship.

Most of that run came under Zmago Sagadin, a Slovenian coach who was as legendary for his fiery temperament as for the success of his squads.

“He was kind of the Bob Knight of Slovenian basketball: quite tough, demanding, disciplined,” Boris says. “But I think he left in all of us a lot, especially work ethic, just to prepare, to respect basketball.”

In 1996, Boris signed with SIG Strasbourg in France. At 23, he led the club in scoring (19.6 points per game) as an aggressive, hard-nosed guard. That performance drew the attention of Ivica Dukan, a Croatian scout best known for helping the Bulls uncover and acquire Toni Kukoc.

After that season, Ivica invited Boris to join Chicago’s squad at the Rocky Mountain Revue summer league in Salt Lake City. Boris, of course, accepted. Like so many Europeans hoopers who came of age in the 1980s and early 1990s, he had idolized the late Drazen Petrovic (so much so that he tattooed Drazen’s jersey No. 3 on his shoulder), while admiring Michael Jordan from abroad. Here was Boris’ chance to not only follow in Drazen’s footsteps, but also potentially do so alongside MJ.

Boris would also vie to be one of the first Slovenians to set foot in the NBA. Several years earlier, Jure Zdovc, who played with Boris on Olimpija, tried out for the Los Angeles Lakers, but didn’t make the final roster out of training camp. Marko Milic, another former teammate of Boris’, seemed to have the inside track in 1997, since the Philadelphia 76ers had selected him in the second round of that year’s draft before trading his rights to the Phoenix Suns.

That was all before Boris struggled so mightily at the outset in summer league that he didn’t think he’d make it to Chicago.

“I remember, the first few games, I played like shit,” he says, “and then I think last game, I got to play really, really well. For some reason—whether it was Ivica Dukan, who really believed in me—[the Bulls] gave me a chance to call me also to the veterans’ camp.”

And, in turn, to shoot his shot against Michael.

In 1995, Boris was visiting Chicago when he got his first glimpse of Michael in the flesh, during a Bulls game at the United Center.

“It just was unbelievable,” Boris says. “And for me, being there was a dream come true.”

Two years later, he was back in Illinois, realizing an entirely different fantasy.

Not just training with Michael, but also trading barbs with one of the masters of trash talk.

“Even Michael joking with me, ‘Drazen is your idol,’” Boris says. “And actually, I was very proud to tease him [with] that. ‘Yes, Drazen is the best ever’ or, you know, always joking with Michael about that. So it was special.”

So, too, was the opportunity to be around one of the greatest teams of all time. To see the quiet professionalism behind the public antics of Dennis Rodman. To witness how Phil laid the foundation for the Bulls’ presumptive return to the NBA Finals.

“Even when we played these preseason games in Paris, it was all preparation to win the championship, like all the games, every practice,” Boris says. “Even back then, I understood everything for them was always about winning everything. It was not about one game. And even in every practice, it was always focused on small details that will come out in the biggest games. So from that end, I think that was a special team.”

Boris barely saw Scottie Pippen, who sat out the preseason and nearly half of the regular season after delaying offseason surgery amid a contract dispute with the organization. Nor was he privy to the drama between Phil, Michael, Scottie and general manager Jerry Krause that’s taken on new life.

“I was such a young kid when I was with them,” Boris says. “I had no idea.”

While he was well aware that his chances of earning a roster spot in camp were infinitesimal, Boris nonetheless soaked up every ounce of the experience that he could.

Playing preseason games at iconic arenas like Allen Fieldhouse at the University of Kansas and the “Dean Dome” at the University of North Carolina. Watching how fans mobbed the Bulls wherever they want, clamoring for a piece of Michael. Even lugging the team’s bags, like any dutiful rookie.

“I loved it, man,” Boris says. “I was nobody there. I didn't care. I really didn't.”

The McDonald’s Championship was particularly special to Boris—not just because he got to pal around Paris with the two-time defending champions, or that he scored seven points during garbage time of Chicago’s 104-78 win over Olympiacos to secure the exhibition title, though those were all memorable moments for him.

During that final game, Boris had gone hard to the rim and been fouled even harder by one of Olympiacos’ players. Afterward, Michael, cameras and sycophants hot on his tail, walked over to Boris to offer a bit more good-natured ribbing.

“Hey,” MJ told him, “your [European] guys didn't let you dunk!”

Though the Bulls didn’t have room for Boris on their roster at the end of camp, they wanted to keep him close by, in case of a roster emergency. And had Boris bought into Chicago’s plans for him, he might have returned to Europe with a ring.

Before leaving the Berto Center, the Bulls’ previous practice facility in Deerfield, and heading home, Boris stopped into Jerry Krause’s office for one last goodbye. The GM gave him a hug and made him an offer. Jerry could get Boris a spot with the Continental Basketball Association’s Chicago Rockers. If the Bulls suffered a serious injury that season, especially to another of their perimeter players, Boris would get first crack at filling in.

Two weeks into the 1997-98 season, Steve Kerr hurt his ribs and sat for almost a month as a result.

By then, Boris was already long gone. Rather than bide his time in American basketball’s minor league, he had gone back across the Atlantic to sign a guaranteed contract with Élan Béarnais Pau-Orthez, a French powerhouse in the EuroLeague.

Instead, the Bulls brought in Rusty LaRue, an undrafted rookie out of Wake Forest who had also competed in training camp. Though Rusty only played 14 games in Chicago that season, he earned a championship ring and would go on to play 84 more games in the NBA with the Bulls, Utah Jazz and Golden State Warriors.

“Looking back, maybe that was a mistake,” Boris says of his decision to return to Europe.

Boris, meanwhile, spent several years battling knee problems overseas. He played a total of 19 games between the fall of 1997 and the spring of 2000.

After a series of surgeries on his troublesome knees, Boris returned to form at a high level in Europe. In the fall of 2000, he signed with Montepaschi Siena in Italy’s Serie A league. He paced the team in scoring for two straight seasons and led Siena to the 2002 FIBA Saporta Cup championship—which he lists as his proudest achievement in basketball.

“It was probably where I played best basketball and probably was one of the best players,” he says, “if not the best player.”

Though the pinnacle of his playing career had all but passed, Boris still had plenty to give to the game, especially as far as Slovenia was concerned. Beyond his five appearances with the national team in EuroBasket, Boris’ path continued to cross with those of his home country’s future stars in the professional ranks.

In 2003, he and Beno Udrih were both set to join Olympiacos in Greece. Boris had already signed by the time the promising then-21-year-old arrived.

But an arcane rule in the Greek A1 Basketball League pertaining to imported players left Beno in limbo, and ultimately led to him signing with BC Avtodor in Russia before embarking on a 13-year NBA career.

Still, Beno spent a month practicing and traveling with Olympiacos. He and Boris connected over their shared Slovenian heritage, and Boris gave Beno a glimpse of the competitive drive and nearly maniacal commitment to health and fitness that helped him succeed as a pro.

There was one road trip, in particular, that stuck with Beno. He was traveling with Olympiacos in Spain for a game from which Boris was held out, without any explanation from the coach. But Boris had prepared as though he were going to play—and, thus, was still wired afterward.

So before the two Slovenians went out for their postgame dinner, Boris was in Beno’s hotel room, pumping out hundreds of pushups and situps.

“I was, like, ‘What are you doing? Let's go, man,’” Beno says. “He's, like, ‘I gotta get this energy out, man. I'm hype, like, I didn't play. I don't know why I have all this energy. I gotta get it out.’"

Goran Dragic saw much of the same obsession, even at the end of Boris’ playing career. Goran was a 21-year-old on the cusp of his own jump to the NBA when he teamed up with Boris, then approaching his mid-30s, on Olimpija for the 2007-08 season.

For Goran, Boris was among a handful of Slovenian hoopers who had inspired his own career by showing that his countrymen could compete at the highest level.

“That was a big deal back then that Boris got invited to Chicago Bulls training camp,” Goran says. “Everybody knew in Slovenia.”

What they didn’t know—and what Goran got to see behind the scenes—was the hard work that went into Boris’ success. Though basketball’s collective toll limited Boris to just 68 total minutes across four games during the 2007-08 season, Goran observed his teammate lift weights, attack his rehab and watch what he ate as though he were still a star.

“We will go into some restaurant that we have free lunch, and he would always order food with no sauce and always pay attention on how to eat healthy,” Goran says. “And man, he was a working maniac, if I can say it like that. He was always last guy leaving the gym, always playing one-on-one and try to be the best player he can.”

If Boris had had his way, the legend of Luka Doncic may well have begun in Slovenia rather than Spain.

Boris was a contemporary of Luka’s father, the Slovenian standout Sasa Doncic. Boris and Sasa played together on their country’s national team and, later, during Boris’ final season on Olimpija, when eight-year-old Luka could often be spotted running around the court in Ljubljana.

“We competed together through all our young years,” Boris says of Sasa, “so I got to know Luka when he was a little kid always around his father.”

Boris’ eldest son, Domen, also came up a year behind Luka through the Slovenian national team’s youth program. While Boris intended for Domen to pursue his passion for basketball through a more conventional domestic route, Luka's mother, Mirjam, let him leave his home country to join Spanish powerhouse Real Madrid at the age of 13.

Of course, Luka did just fine in Spain. At 16, he became the youngest to ever play for Real Madrid and made a strong impression, even in his first game as a pro.

“Immediately, he scored a three-point shot from the corner against Malaga, which is a top team in Spain,” Boris says. “So I mean, this guy is just phenomenal.”

Luka aside, Boris turned out to have a shrewd eye for talent. After retiring from basketball as a player in 2008, he embarked on a career as an agent for professional basketball players in leagues outside of the NBA.

“I knew I wanted to stay in basketball,” Boris says. “I just could not imagine myself having a boss over my head no more because being a basketball player and traveling, you always depend on somebody or you always have to listen to the coach or whoever is giving you this, this, this and that.”

Though Boris appreciated the freedom of his new profession, he struggled early on. The accomplishments from his playing career carried little (if any) weight with prospective clients.

“It was tough, the first two, three years, especially on the ego part,” he says, “because you have to learn that the players are now treating you like nobody.”

But Boris wasn’t alone. He frequently consulted (and occasionally commiserated) with Vera Vakulenko, a decorated basketball executive who had helped the Russian club CSKA Moscow make a record six consecutive EuroLeague Final Four appearances, including championships in 2006 and 2008.

Before returning to Slovenia to finish his career, Boris spent two seasons with BC Khimki, CSKA’s biggest rival in both the EuroLeague and Russia’s VTB United League. Despite the on-court tensions between the teams, Vera came to Boris’ aid when he tore his ACL there.

“She helped me a lot with the hospital and with everything,” he says, “so we became friends.”

That friendship carried on, even after they both left Russia. Not long after Boris retired in Slovenia, Vera left Moscow for a job with a Polish EuroLeague club called Prokom, now known as Arka Gdynia. As Boris began contemplating starting his own representation business, he turned to Vera for advice on the business of basketball.

When Vera grew weary of her role in Poland, Boris suggested she move to Slovenia to help found ProStep Sports Agency. Between Boris’ ability to connect with players on their level and Vera’s understanding of the business from a management perspective, they built ProStep into a successful enterprise, representing the likes of Slovenian big man Primoz Brezec before he came to the NBA as a first-round pick in 2000.

“She helped me a lot,” he says. “She was my mentor.”

Though Vera passed away two years ago due to heart and lung issues, Boris and his colleagues have continued to build on the firm foundation that she helped to establish. ProStep’s roster features a number of former NBA players now competing overseas, including JaKarr Sampson, Antonio Blakeney, Deng Adel, Davon Reed, Arnett Moultrie and Brandon Sampson. Much of that clientele stems from ProStep’s partnership with Verus Management, which represents Terry Rozier, Victor Oladipo, Kevin Knox and Derrick Jones Jr., among others, in the NBA.

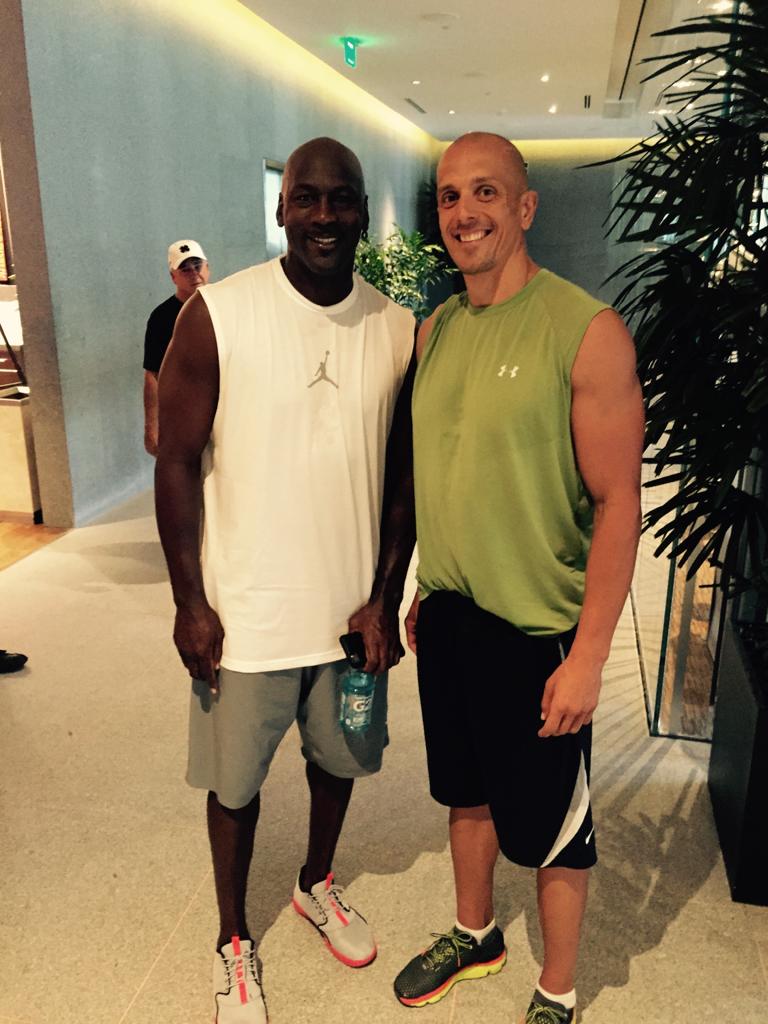

Boris recently reconnected with Michael Jordan during NBA Las Vegas Summer League. (Courtesy of Boris Gorenc)

As much as Boris cherishes his time with the Bulls, he has few (if any) keepsakes from that training camp.

“I might have shorts from a game that we played in Paris,” he says. “But the rest, I just gave everything to my friends.”

Boris has at least one bit of MJ memorabilia, albeit not from “The Last Dance.”

In recent years, Boris has become a regular at the NBA’s Las Vegas Summer League, where he’s gone to connect with clients and scout players. In 2017, he went for a lift at a hotel fitness center when, lo and behold, he happened upon MJ mid-workout.

Though Boris hadn’t seen or spoken with Michael in 20 years, “he remembered immediately,” Boris says.

"You're in good shape," Michael told him.

"Yeah," Boris replied. "Now, I think I can finally beat you."

“We took a picture and it was really fun to reconnect with him,” Boris says now.

The arrival of The Last Dance has brought many more indelible images of Michael flooding back into Boris’ memory. The series, too, has occasioned calls and text messages from friends and family, as well as heaps of interview requests from Slovenian media outlets, though he’s turned them all down.

“I just didn't feel right to go anywhere and to talk about this because I feel like it's mine and I don't want to share it,” he says.

What’s more, Boris was late to start the series. He had to borrow his brother’s Netflix password in order to watch.

From what he’s viewed so far, Boris says it’s “very interesting to see it again” and “great to see” himself in it, however briefly, in Episode 1 when the Bulls go to Paris. He’s learned a lot about what was going on behind the scenes back then as well.

More than anything, “it's just great to see Michael,” he says. “I mean, maybe we all forget a little bit how good he really was, how special he was.”

Boris is as wrapped up in tracking the coronavirus as anyone these days. Only in the past few weeks, since Slovenia began lifting its nationwide lockdown, has he been able to resume any semblance of a normal life. Between advising his clients across Europe whose careers have been halted by the pandemic and looking after his five kids—including Domen, who’s now 19 and had been competing in the top level of professional basketball in Slovenia—Boris has been a busy man during these uncertain times.

So, like millions around the world, he’s turned to The Last Dance as an escape into nostalgia. Except, in his case, for a short time he actually lived it.

Josh Martin is the Editorial Director of CloseUp360. He previously covered the NBA for Bleacher Report and USA Today Sports Media Group, and has written for Yahoo! Sports and Complex. He is also the co-host of the Hollywood Hoops podcast. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Instagram

Twitter

Error: Could not authenticate you.

Facebook

Subscribe