Before He Became the Michael Jordan of Hungary, Kornel David Competed with ‘The Last Dance’ Bulls

Kornel David was in awe. There was Michael Jordan—the best basketball player in the world, arguably the greatest one who ever lived, and the most famous person on planet Earth—in the flesh. Kornel had grown up watching MJ’s Chicago Bulls every week on TV in his native Hungary. Never did he think he would breathe the same air as Air Jordan.

“For us to see him in person, it's, like, I don't know what to say,” Kornel tells CloseUp360. “It's like God is walking in.”

But Kornel wasn’t just another admirer at an NBA arena. For the next few weeks, he would be competing for a spot on Michael’s team, as an invitee to the Bulls’ training camp at the Berto Center in 1997, ahead of the season that’s now been immortalized in ESPN’s The Last Dance docuseries.

During that media day in Deerfield, Illinois, though, Kornel was more akin to a fan—anonymous to MJ and caught up in the aura of an icon—while observing alongside Boris Gorenc, another training camp combatant from abroad.

“[Michael] just walked past us,” Kornel says, “and we just keep walking behind him.”

Michael approached the podium, addressing questions from a throng of reporters as hundreds of cameras clicked and flashed like a cloud of fluorescent beetles. All the while, Kornel took mental snapshots of his own.

How Michael walked. How he talked. How he handled the suffocating swell of attention.

When Kornel showed up for practice the next day, he continued cataloguing details in his mind.

How MJ put on his iconic signature sneakers. How he tied his shoelaces. How he wore shorts from the University of North Carolina, MJ’s alma mater, under his practice shorts.

“I really wanted to know why this guy is so good,” Kornel says. “I tried to figure it out.”

Then, practice began, and Kornel saw close up what separated Michael from the rest.

Okay, this is just different, Kornel thought to himself. A totally different level.

What Kornel witnessed while in training camp with the Bulls—from the most minute details to the grand scope of MJ’s celebrity—would stick with him throughout a journey that led him to become, for lack of a less hyperbolic term, the Michael Jordan of Hungary.

Hungary is about as central as Central Europe gets. The Danube River, immortalized in Johann Strauss II’s waltz “The Blue Danube,” starts in Germany, drains into the Black Sea by way of Ukraine and, along the way, divides the Hungarian capital of Budapest between the Buda and Pest sides of the city.

Thanks, in part, to that location, Hungary has long been a formidable sporting nation on the global stage. Despite having a population of fewer than 10 million people, Hungary has claimed 498 medals at the Olympic Games—the 10th-most of any country—giving it the fifth-highest medal count per capita in the world. Budapest was in the running to host the 2024 Summer Games before Paris won the bid.

Hungary also borders the former Yugoslavia, a basketball powerhouse that split into hoops havens like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia and Macedonia in the 1990s.

Yet, only one Hungarian—Adam Hanga, a second-round pick of the San Antonio Spurs in 2011—has ever been selected in the NBA draft. And only one Hungarian has ever actually played in the NBA.

His name is Kornel David.

For most of his early life, Kornel looked like a longshot to even pick up basketball, much less excel at the sport. Though his mother hooped a bit in college and his brother played at a young age, Kornel gravitated instead towards another of Hungary’s sporting specialties: soccer.

It wasn’t until he hit a teenage growth spurt (and literally outgrew soccer as a result) that Kornel turned his attention to basketball. With his size and athleticism, he proved to be a natural. That, in turn, sparked an appreciation of the sport.

“I started to enjoy it,” he says, “and I think everything went fast after that.”

In the late 1980s, Kornel began training with the junior squad of Budapest Honved SE, a storied club in the Hungarian capital. He made his on-court debut during the 1987-88 season, signed with Malev SC before the 1988-89 season and returned to Budapest Honved for the 1990-91 campaign.

Kornel went undrafted by the NBA in 1993, though that hardly deterred him. The following season, he helped lead Budapest Honved to the 1993-94 Hungarian Championship—the team’s 31st such title (it has since added two more). Following that run, Kornel decamped to Alba Fehervar in the central Hungarian city of Székesfehérvár, where he became a 6’9” scoring star while carrying the club to its first domestic title.

At 26, a decade after picking up basketball, Kornel had not only reached the pinnacle of the sport in Hungary, but also practically built a home on that mythical mountaintop. Being the biggest fish in a small hoops pond, though, had its limitations.

“A small country, small gyms, everything is small, basically,” he says, “but it's a competitive league, so being a champion here, I was really proud of it.”

Still, Kornel wanted to test himself in a bigger basketball market. Definitely elsewhere in Europe. Perhaps even in Spain or Italy.

“I never imagined to be in the NBA,” he says.

In June 1997, Kornel was still basking in the glow of his second Hungarian title when he got the call of a lifetime. It was Jerry Krause, the famed (and now infamous) general manager of the Bulls.

Jerry had heard about Kornel from his contacts in Europe. As a 6’9” forward with above-average athleticism, scoring skill and a resume of team success, Kornel had the makings of another gem for Jerry to uncover across the Atlantic.

But Jerry wanted to see for himself, so he invited Kornel to come to Chicago for a mini-camp. The catch: Kornel would have to pay his own way—flights, hotels, everything.

So Kornel bought a plane ticket and left Hungary for Illinois. He performed well enough at the Berto Center to earn an invitation to play with the Bulls at the Rocky Mountain Revue in Salt Lake City. Kornel continued to turn heads with his size, skill and hustle in Utah—so much so that Jerry decided to bring him back to Chicago in the fall.

The Bulls gave Kornel no assurances, other than that he would get to practice with the team, learn from the five-time champions, study Phil Jackson’s famed triangle offense and, perhaps, brush up on his English.

“I was happy,” Kornel says of the invitation to training camp, “but I was nervous.”

He flew back to Chicago as soon as he could and started working out at the Berto Center immediately. He knew his odds of becoming a regular-season Bull were slim, but he wanted to give himself the best chance he could to make the roster.

“I don't know what to expect, but one thing for sure in my mind: I want to be the last guy in that camp,” he says. “I wanted to show them I can play.”

On the first day of Bulls training camp in 1997, the entire team (save for Dennis Rodman, who came to camp late) gathered inside the film room at the Berto Center. As was customary, everyone had to stand up in front of the group and introduce themselves.

Most of the players didn’t have much to say and didn’t have to say much because, well, they already knew each other. Of the 15 men who had helped Chicago claim its fifth Larry O’Brien Trophy the previous spring, 12 had returned to round out a second three-peat.

Michael and Scottie mustered minimal introductions for themselves, offering little more than “five championships.” When Kornel’s turn came, he stood up, introduced himself and said, “I’m here from Hungary.”

As Kornel recalls, Michael was befuddled.

“Another international player?” Michael said.

The Bulls were already one of the more worldly teams in an NBA that hadn’t yet gone ga-ga for global basketball. In Chicago, there was Luc Longley and Bill Wennington, who’d hailed from Australia and Canada, respectively, before playing college ball in America. Steve Kerr was American, too, though he’d been born in Lebanon before growing up in Los Angeles. And, of course, there was Toni Kukoc, the Croatian sensation whom Kornel had idolized—but who’d unwittingly drawn the ire of Michael and Scottie for being “Jerry’s guy.”

Even though Kornel might’ve looked like another of Jerry’s pet projects from Europe, Michael and Scottie didn’t torture him on the court like they had done to Toni at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona. In Scottie’s case, he couldn’t do much of anything at that point, since he missed all of training camp (and much of the regular season) after delaying offseason surgery amid a contract dispute with the Bulls.

Michael, on the other hand, barely spared any energy or words for any of the rookies, let alone an entire antagonism for one anonymous face.

What little interaction Kornel had with Michael was mostly innocuous, though revelatory nonetheless. After one practice, in particular, Kornel was in the locker room when MJ pulled a box out of his stall and opened it up to reveal a selection of what appeared to be high-quality cigars.

“He just lights up the cigars and I just opened my eyes and maybe my mouth was open, too,” Kornel says. “He just told me, ‘Hey, this is the smoking area. Sorry, kid,’ and walked by.”

More eye-opening, still, was how MJ went about his business, both on and off the court. Whatever he was doing around and with the team—from shooting free throws and three-on-three scrimmages, to card games on the team plane—he was locked in and trying to win.

“Even the warm-up for running, he was so focused and he was competing like crazy,” Kornel says, “and everything went so easy for him.”

That Michael appeared to float along and still dominate showed Kornel just how wide the gap still was between the NBA and the rest of the world, just five years after the Dream Team took the Barcelona Olympics by storm. Though Kornel was no slouch on the court, and was as good a basketball player as Hungary had yet produced, he had to strain himself to keep up with his counterparts in Chicago.

The intricacies of the triangle offense only added to the challenge. While most of the players in camp had spent years moving through its hundreds of reads, Kornel had to play catch-up, all while putting his limited (but growing) grasp of English to the test as he listened intently to Phil Jackson and the offense’s creator, the late Tex Winter.

Not that the Bulls’ training camp was all struggle and strain for Kornel, by any stretch. With time and attentive effort, he picked up the principles of the triangle and earned the opportunity to demonstrate some of his skills within its confines.

“They gave me the chance to learn the system being on the court with them, just like in any other rookies,” he says. “Sometimes, you’re watching more in practice and you will be more clear [on how the triangle works].

“I didn't feel like I'm an outsider. I felt like I'm a part of the team, as a rookie.”

The Bulls didn’t entirely treat Kornel like a rookie either—other than the occasional run for coffee or donuts, anyway. He got to hang around Toni, whose path from European stardom to NBA success inspired his own journey. He got a kick out of Dennis’ outlandish outfits, from colorful pants and translucent shirts to full-on police uniforms (though he rarely heard from “The Worm,” who mostly kept to himself aside from his conversations with assistant trainer Wally Blase). And he saw how Phil managed the team’s cast of characters to create a cohesive chemistry.

Though an ankle injury kept him from traveling to Paris with the Bulls for the McDonald’s Championship, Kornel got to be a part of Chicago’s matchup against Allen Iverson’s Philadelphia 76ers at the “Dean Dome” on the campus of the University of North Carolina. He was struck by the electricity that trailed the team throughout MJ’s triumphant return to his alma mater.

“It was just like a Beatles concert,” Kornel says. “When we arrived and our plane just landed, it's hundreds and hundreds of people everywhere, running in the boots.”

Of course, that frenzy was almost entirely for Michael. Kornel saw how deftly this walking icon handled his celebrity, how he stayed focused on the task at hand and didn’t let the world’s adoration of his greatness distract him or get to his head.

“What I learned is, basically, it doesn't really matter where you're at in your career as a player,” Kornel says. “Win or lose, you still need to be hungry and motivated because that's something you keep. You do your routine, you do your things, which you believe in, and then you always have to find the new tools to get better.”

Kornel returned to Hungary in December 1997, with little fanfare upon arrival. Some folks in Budapest’s basketball community made note of his sojourn to the United States, but beyond that, his preseason stint with the Bulls had barely registered.

Back in Chicago, though, Kornel’s departure had garnered significant attention (and ire) from at least one person: Jerry Krause.

Kornel was among the last players cut, along with Boris Gorenc, Dante Calabria and Rusty LaRue, before the regular season began. There were no roster spots to spare in Chicago, and there hadn’t been any from the beginning. But Jerry knew to be prepared in case of a major injury to a player under contract, and saw those three as valuable potential fill-ins.

So, drawing on his long-standing connections to and affinity for the Continental Basketball Association (CBA), Jerry offered minor-league assignments to those who had persevered through the Bulls’ camp.

Boris declined an invitation to play for the Chicago Rockers and returned to Slovenia. Dante and Rusty accepted offers to play for the Fort Wayne Fury and Idaho Stampede, respectively.

“Jerry told me at that time, ‘Kornel, you have to play, learn the culture, learn the language and the terminology, the basketball and everything,’” Kornel says. “‘You have to stay because you never know, you might get a call up during the season.’”

Kornel heeded Jerry’s advice and, after rehabbing his ankle in Chicago, joined the Rockford Lightning. As small-time as basketball in Hungary had been, he found the CBA to be even less inviting. The long bus rides, the industrial towns, the style of play—all of it was a far cry from the taste of America that Kornel had gotten in Chicago, and was cause for culture shock compared to what he knew back home.

“The CBA is really a tough, tough league, tough environment, tough organization, really small money,” he says, “but a lot of players want to show themselves and keep the chance to go to the league.”

The allure of an opportunity to rejoin the Bulls—even just to ride the bench—was enough for Kornel to try his luck in Rockford. But after going through training camp with the Lightning, it quickly became clear that his opportunities would be limited there. He played just a few minutes over the first couple games in Rockford and, with teams in Hungary recruiting from abroad, decided instead to leave the CBA and head back to Budapest.

“I made a big mistake,” Kornel says. “Well, I didn't know that at that time it was a mistake.”

Had Kornel stuck it out in Rockford a little longer, he might’ve gotten called up to the Bulls when Steve Kerr suffered a rib injury in November 1997. Instead, the call went to Rusty, the only former Chicago training camp invitee who was still in the CBA at that time. Rusty went on to finish the season with the Bulls, albeit with only 14 appearances, and came away with a championship ring.

Kornel got a ring, too, just not in the NBA. He led Alba Fehervar to its second straight Hungarian title and his third in his home country.

Doing so, though, seemed to come at a cost to Kornel’s potential future in the NBA. His decision to head back to Hungary had angered Jerry, who had expected Kornel to stay and hoped to develop him. Hoops hell hath no fury like a GM scorned.

“I left and Jerry got really mad at me and was really pissed,’” Kornel says. “He said he doesn't want hear my name again.”

But Kornel wanted back in. Through his agent at the time, he pleaded with Jerry to give him one more chance. With the Bulls facing a rebuild in the wake of “The Last Dance,” Jerry relented. Kornel would have to prove himself in summer league again, and again, he did.

That same summer, a bitter dispute between the NBA’s owners and players led to a lockout that shortened the 1998-99 season to 50 games and delayed the start until February. Kornel went back to Hungary to ride out the delay on the court with Alba. Come January 1999, the league reopened, the Bulls signed Kornel and he was on his way back to Chicago for an entirely different experience.

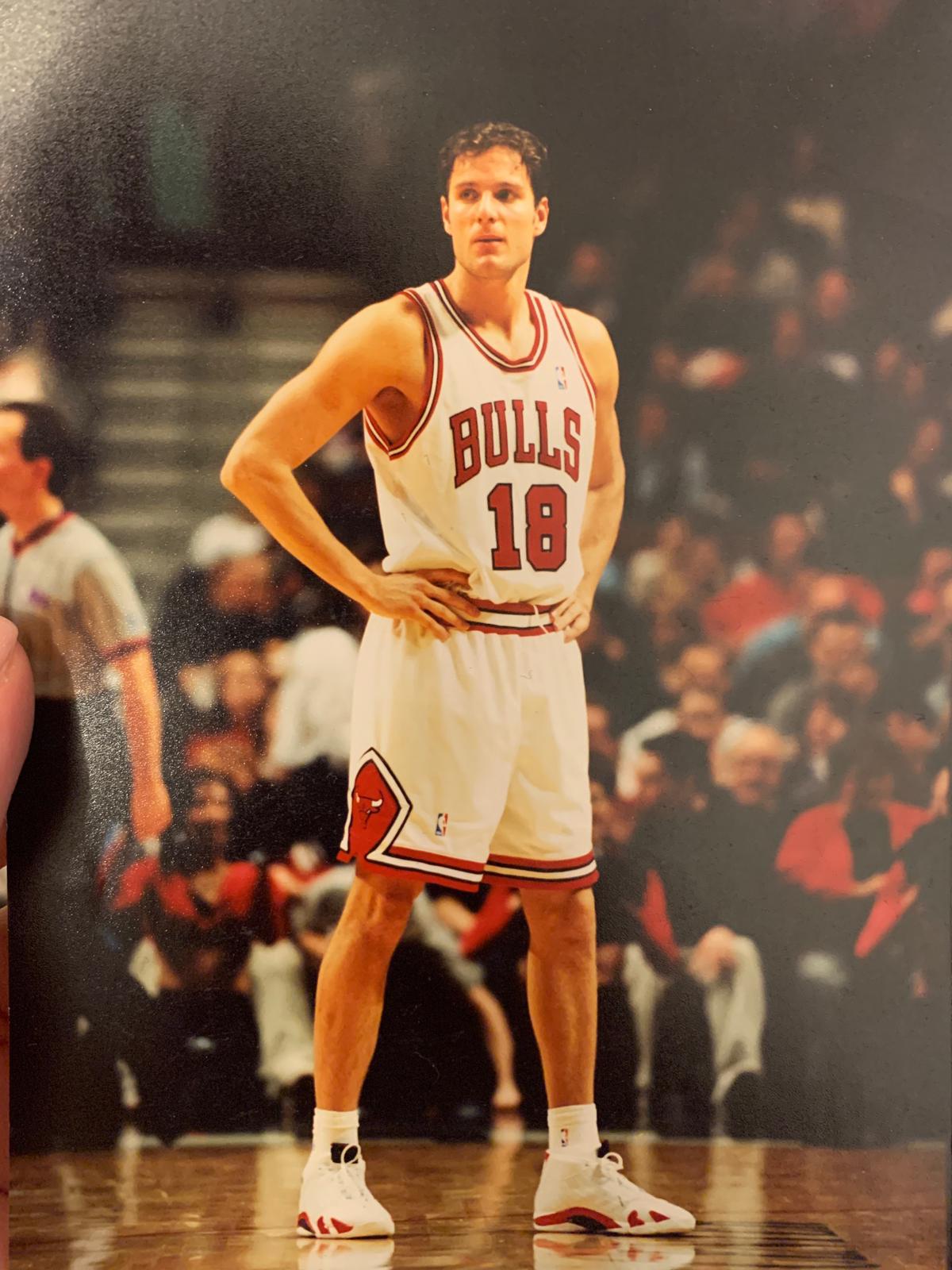

Kornel David rejoined the Chicago Bulls for the strike-shortened 1999 NBA season. (Courtesy of Kornel David)

The 1999 season was, in many respects, a low point in the history of the Chicago Bulls. After dominating the NBA for most of the 1990s, the group that convened at the Berto Center was nearly unrecognizable.

Michael had retired again. Phil had gone into hibernation in Montana. Scottie had been traded to the Houston Rockets. Dennis and Jud Buechler were released and signed elsewhere. Steve and Luc were dealt to teams that gave them raises.

What had been one of the NBA’s most experienced rosters was now one of its youngest. And it showed.

The Bulls saw their winning percentage plummet from a league-best .756 in 1997-98 to .260 in 1999, the third-worst mark in the Association. Chicago lost by an average of 9.5 points per game in 1999, which ranked at the bottom of the league. That April, the Bulls scored a measly 49 points in 48 minutes during a 33-point loss to the Miami Heat, marking the most anemic offensive performance of the shot-clock era.

For all the misery the Bulls and their fans endured, the lockout-shortened campaign was a landmark of sorts in Kornel’s career. Though he was still technically a rookie, he came into training camp with a confidence and feeling of familiarity forged from having competed in Chicago during the fall of 1997.

He had already built rapports with Toni, Rusty, Ron Harper, Randy Brown, Keith Booth and Dickey Simpkins from the previous preseason. Bill Wennington took Kornel under his wing and showed him around town. Tim Floyd, the Bulls’ first-year coach out of Iowa State, had tried to recruit Kornel to the University of New Orleans years earlier. And unlike fellow rookies Corey Benjamin and Cory Carr, Kornel was 27 years old, a man matured by his success overseas and travails in the United States.

Amid that amalgamation of championship-tested veterans and unproven youngsters, Kornel carved out a consistent role for himself. He played in all 50 games, with six starts, 14 double-digit scoring games and a pair of double-doubles. All the while, he got to witness Toni, his European hero, post career highs in points (18.8), rebounds (7.0) and assists (5.3) as Chicago’s No. 1 option.

“He was absolutely killing, absolutely was fantastic,” Kornel says of Toni. “He was a leader of that team. He played great, and it was a joy to play with him.”

But the losses took a toll on Kornel, as they did on every member of that Bulls team. As the defeats piled up, the veterans checked out, the younger players tried to pad their own stats and Tim’s struggles acclimating to the NBA continued.

Kornel spent the summer of 1999 in Chicago, working out and building his body with the hope that he could expand his role with the Bulls the following season. Instead, his opportunities dwindled, subsumed by the tides of Jerry’s rebuild. In that year’s draft, the Bulls selected Elton Brand with the No. 1 pick, Ron Artest at No. 16 and Michael Ruffin at No. 32. All three would take precedence over Kornel in a frontcourt that already returned Toni and Dickey, and welcomed back Will Perdue, a mainstay from the team’s first three-peat.

“I found myself in the trap,” Kornel says, “because I worked so hard and they drafted those guys who turned out to have pretty good careers.”

Kornel played 32 more games with the Bulls before they waived him in early January 2000. Shortly thereafter, he signed a pair of 10-day contracts with the Cleveland Cavaliers. He returned to play summer league with the Toronto Raptors that year and performed well enough to earn an invite to training camp and, eventually, a free-agent contract, only to be dealt to the Detroit Pistons ahead of the trade deadline in February 2001.

At each of those stops, Kornel got to evaluate a potential “Air Apparent”: Vince Carter in Toronto and Jerry Stackhouse in Detroit. As much as Kornel admired Vince’s talent, athleticism and knack for taking care of his body, he saw in Jerry an approach to the game more akin to the one that set MJ apart.

“Stackhouse was really a hunter,” Kornel says. “He just went after everybody. MJ was head and shoulders above everybody, but in terms of mentality in being a dog out there who wants to prove himself, doesn't matter the situation around him, it's more Stackhouse like MJ than Vince.”

Though Vince and Jerry both had outstanding NBA careers, neither quite lived up to the hype of being the league’s next great Tar Heel. In fairness to them, the standard MJ set was nearly impossible for anyone to live up to—including Michael himself, when Kornel saw him again ahead of his comeback with the Washington Wizards in 2001.

“He was different,” Kornel says. “He still worked so hard just to get in shape and work on individual stuff. He had his own trainer and everything, but in that time I think he was in a different mindset.”

In Chicago, Michael came into every camp with championship expectations. In D.C., he was aiming to drag the Wizards into the playoffs and make the franchise relevant after more than a decade of mediocrity.

Kornel didn’t make Washington’s final roster, but his previous experience with MJ earned him early recognition from the GOAT.

“He came up to me right away and he told me, ‘Okay, let's go, let's play three-on-three,’ just before the camp,” Kornel says. “I don't know if he still remembers that. I remember, for sure.”

Kornel’s final attempt at sticking in the NBA came in 2003. He joined the Boston Celtics’ squad for the Reebok Pro Summer League at the Clark Athletic Center on the campus of the University of Massachusetts. There, he came across a teenager touted as basketball’s post-Jordan torchbearer: LeBron James.

“I was so excited to just play against him,” Kornel says. “I wanted to see him in person.”

If only to add to his long-running catalogue of what made Michael so great.

After stints with four different NBA teams, Kornel had lived a reality that was beyond what he could’ve dreamt, coming from a basketball backwater like Hungary. Those bona fides boosted his resume with some of the top clubs in Europe. But wherever he went, he had to prove himself all over again.

“I'm not from Lithuania, not from Russia, not from Serbia, not from Spain, not from great big basketball countries or whatever,” Kornel says. “I'm from Hungary, so everywhere I played, I was always a Hungarian. And what is the Hungarian doing in Lithuania? What is a Hungarian doing in Spain?”

In short, he was there to win. In Lithuania, he won a league championship with BC Zalgiris, one of the continent’s most decorated clubs. In Spain, he piled up domestic cups and reached back-to-back EuroLeague Final Fours with a Saski Baskonia squad that featured a handful of eventual NBA veterans, including Luis Scola, Tiago Splitter, Andres Nocioni, Pablo Prigioni and Jose Calderon.

“They always asked me, ‘How is it in the NBA?’” Kornel says.

They wanted to know about the physicality in the world’s best basketball league, about the impact of a deeper three-point arc and a wider lane, and about the lavish lifestyle that players lived off the court.

Kornel’s advice panned out. That aforementioned quintet went on to play a combined 43 seasons in the NBA, with Tiago taking home a title as a member of the Spurs in 2014.

As those teammates made their way across the Atlantic, Kornel began thinking about his own future in the NBA. During his second season with Baskonia, he took an online course in scouting and management. He kept in touch with his friends and associates in the NBA. Following his retirement from basketball in 2008, on the heels of a two-year stint with CB Gran Canaria in Spain, he landed another gig in the league—as a scouting intern with the Cavs.

After a year and a half with Cleveland, he moved into an international scouting role with the Phoenix Suns for three years. Towards the end of his tenure with the Suns, Kornel got a tip from a contact in Greece about an intriguing teenager competing in a lower-level league there.

“Everybody was wondering, “Okay, this kid, I heard about him. He's from Greece, but he's not really from Greece. He doesn't have a Greek passport,’” Kornel says. “He did not play at that time in any European competitions, in any youth system—not under 16, under 18, nowhere. So seeing him competing against the same age group, it was impossible to see him because he never competed against those guys.”

So, in the fall of 2012, Kornel flew to Athens to see what all the fuss was about. He was the only NBA scout in the building to see a teenager named Giannis Antetokounmpo.

“He was skinny, tall and he could handle the ball,” Kornel says. “He was head and shoulders better than the other ones, but he was a humble kid and he worked hard.

“But predicting him to get where he is now, it was so difficult.”

When Kornel went back to Greece in the winter, he spotted at least three or four other representatives from NBA teams watching “The Greek Freak.”

“It's really hard to keep it secret,” Kornel says.

That got out quickly when the Milwaukee Bucks selected Giannis with the No. 15 pick in the 2013 NBA draft. By the time Giannis arrived at the Bucks’ old practice facility, the Cousins Center in St. Francis, Kornel was there, having joined the organization as an international scout after the draft.

Since then, Kornel has tracked Giannis’ rise as basketball’s next global superstar from his home base in Budapest—no trips to dilapidated gyms required.

“I thought he could be special, but the timeframe to when and how long he needs to be that special, it just was a guess,” Kornel says. “And the ceiling where he can be, nobody I think can say that, ‘Okay, this guy going to be an MVP in the league and that good.’”

Kornel is currently an international scout for the Milwaukee Bucks. (Courtesy of Kornel David)

For the last 23 years, basketball has taken Kornel all over the globe, but his greatest impact remains in Hungary. When he returned home after playing regular-season NBA basketball with the Bulls, he was treated as a conquering hero, a rockstar among his people.

“I was all over the place in the media and everything,” he says. “People were calling me to put my face on the billboards and I was everywhere. It was a really big deal at that time.”

With that fame came magazine spreads and localized endorsement deals with Coca-Cola to promote Sprite and Gatorade. But that notoriety also brought Kornel a caliber of fan frenzy that, to some degree, put him in MJ’s shoes.

“It was to the point when you cannot go out there because people are just walking to you and asking you always something,” Kornel says. “It wasn’t cool, really, and I never really was a person who enjoyed it. I'm more a reserved kind of guy.”

Kornel had a platform in Hungary, and he wasn’t about to waste it. In 2000, he founded the David Kornel Basketball Academy (in Hungary, the family name comes before the given name) as a way of growing the game in his home country and helping kids achieve success in life.

“The idea was, let's make the academy, which helps the kids to play basketball, but also for education,” he says.

Beyond basketball, the academy offers English language courses and computer learning as part of an educational curriculum that serves hundreds of boys and girls each year. The club team affiliated with the academy has seen several of its players go on to compete for the Hungarian national team, including Adam Hanga, a former Spurs draftee in 2011.

Since then, Kornel has only added lines to his CV. In addition to scouting for NBA teams, he’s spent the last decade offering commentary and analysis on NBA broadcasts in Hungary. His co-workers in that world came up with the idea to make a film about Kornel’s life, which spawned the 2017 documentary Kornel on Tour.

Kornel has also authored a book about his life and, in 2012, he became the president of Alba. During his first year in charge, the club won its fourth Hungarian championship.

The second season wasn’t quite so successful. Alba fell to sixth in the league and just 2-8 in EuroCup competition. Splitting his time and attention between running a club and pursuing a career in NBA scouting wasn’t working, so shortly after the 2013-14 season, he resigned from Alba.

Someday, Kornel hopes to run an NBA team. To do so, he’ll have to work his way up basketball’s career ladder, to the point where he would be working stateside in a front office.

For now, he has his hands full in Hungary. His older daughter, Dominika, transferred back home after starting her collegiate career at Saint Louis University. His younger daughter, Maja, has gotten serious about her father’s sport of choice in recent years.

“She now kept telling me she wants to play in college in the states and everything,” Kornel says, “so I told her, ‘Oh yeah, well, it's not that easy.’”

In 2017, he became a father for the third time when his second wife, Fruszina, gave birth to their son, Dalton. Getting him to take up hoops may be a bit of a challenge for Kornel. Fruszina, for one, is a professional handball player who hails from a hockey family.

“I put a small basketball in his hands as early as I can,” Kornel says.

He hopes to see Dalton taking steps on the hardwood. In the meantime, Kornel will be busy scouting the world for talent—remotely, of course, during the coronavirus shutdown—and building another professional bridge to the NBA.

And when there’s time enough to reminisce about his playing days, he can turn on The Last Dance. Or, better yet, Kornel on Tour.

Josh Martin is the Editorial Director of CloseUp360. He previously covered the NBA for Bleacher Report and USA Today Sports Media Group, and has written for Yahoo! Sports and Complex. He is also the co-host of the Hollywood Hoops podcast. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Instagram

Twitter

Error: Could not authenticate you.

Facebook

Subscribe