NBA Champion Festus Ezeli Returns to Nigeria to Reunite with Family, Give Back Through Basketball

Mercy Ezeli can’t quite put her finger on it, but there is something familiar about the giant man sitting on her bed. She smiles and squints as she sifts through her faltering memory, searching for an answer. The children and grandchildren who surround her seem to know who he is. After all, they welcomed him warmly into the room.

But at 6’11”, he dwarfs all of them—even those that measure at 6’7” and 6’8”.

“I know you,” she says, looking up at him with a smile. “I know you, but I don’t know you.”

So Mercy turns to her daughter, Uchenna Okafor, who’s by her bedside, and asks, “Who is this?”

“Ifeanyi,” Uchenna replies. “Your grandson, Ifeanyi.”

“Ifeanyi,” Mercy answers, racking her brain. “What do you mean Ifeanyi?”

“Ifeanyi, your grandson,” Uchenna says again. “The son of Festus.”

“What?” Mercy returns, incredulous. “You mean, the Ifeanyi that’s playing basketball in America? Oh my God!”

Yes, that Ifeanyi, the one whom the wider world knows as Festus Ezeli. The one who won an NBA championship with the Golden State Warriors in 2015. The one on whom she hadn’t lain eyes since he was a young teenager, long before he was nearly seven feet tall, let alone a known quantity in the basketball world.

For half an hour, until she grows tired, Festus and his grandmother—”Mama,” as he calls her—hug. They cry. They speak to each other in Igbo, their native Nigerian tongue. They do all they can to fit a decade and a half apart into the 30 minutes they have together.

“I just felt like a little kid when I went and embraced my grandma because I hadn't seen her since I was 13,” Festus tells CloseUp360. “And now, I'm 30 years old, I'm 260 pounds and I'm laying on my 100-pound grandma—less than 100 pounds probably—but 100-pound grandma, and I'm that 13-year-old kid again.”

After spending more than half of his life away from home, Festus was a far cry from that 13-year-old kid. This past summer, for the first time in 15 years, he went home a full-grown man—not only to reunite with family and friends, but also to give back to the game that had pulled him away and given him a life beyond anything that bright-eyed teenager could have imagined.

And what Festus got out of his time in Nigeria just might be the key to another long-awaited return: to the NBA.

Long before he became a professional basketball player in America—and even longer before he returned to Africa as a conquering hero for the continent—Festus was a standup young man in Nigeria. Back in his hometown of Benin City, he went by his birth name, Ifeanyi, which translates to “Nothing is impossible with God” in Igbo. As the oldest of six children to Patricia and Festus Chukwuma Ezeli, young Ifeanyi took it upon himself to be a leader within his own family.

“I've always thought about other people,” Festus says. “I've always thought about the greater good.”

Thinking, too, was Ifeanyi’s forte. Though he was the biggest kid in his neighborhood and inherited his father’s intuitive athleticism, he didn’t care for sports. But his indifference didn’t stop his friends from trying to involve him.

“Get Ifeanyi to come play,” they would shout at one another, whenever they needed a fifth person on the basketball court.

“But then, I'd say, ‘I'm good, I'm not interested,’” Festus recalls. “That was always my thing because sports were really not my thing at the time.”

Instead, young Ifeanyi focused on his studies. He dreamed of becoming a doctor, not a professional athlete.

Education was a cornerstone in the Ezeli household. Patricia ran the Notre Dame Group of Schools in Benin City. His father found success as a distributor for Guinness beer in Nigeria.

“Both parents, they really value education,” Festus says.

In that environment, Ifeanyi excelled as a student—so much so that he skipped from fourth grade to seventh, and graduated from Igbinedion Education Centre at 14. To reward their eldest child for his academic excellence, the Ezelis planned a family trip to visit his uncle, Chuk Ndulue, in Northern California. Chuk, a pediatrician in Yuba City—more than 40 miles north of Sacramento—hadn’t seen his nephew since he was a baby.

So when the Ezelis arrived in 2004, and Chuk saw Ifeanyi stalking around at 6’5” (and growing), he knew his sister’s son could have a future in something other than medicine.

“He was, like, ‘Wow, this is a basketball player right here,’” Festus recalls.

Ifeanyi, though, knew nothing about hoops. Only when uncle Chuk mentioned that the game could earn him a college scholarship in the States, where he could study medicine, did Ifeanyi take notice.

He accompanied his cousin, Ike Okoye, to a practice at Woodcreek High School in Roseville to see what the sport was about. The coaches there thought they had a game-changer on their hands.

That is, until they put a basketball in his.

“I chucked it at the backboard,” Festus remembers.

Everybody in the gym started laughing. They thought it was a joke.

“I didn’t know what was going on,” Festus says.

Still, the family figured it best to keep Ifeanyi with his uncle, so he could pursue his education in America. At that moment, Ifeanyi resolved not to return to Nigeria empty-handed.

“I thought in my head, I wasn't gonna come home until I accomplished something,” he says. “And at the time, I thought that my goal was to become a doctor. Well, you know, just like life happens, things happened.”

Ifeanyi wasn’t exactly a natural on the court. But in time, basketball went from a means to an end, to a passion in its own right.

In 2004, Chuk enrolled his nephew at Jesuit High School, a hoops powerhouse in the Sacramento suburb of Carmichael. Though Ifeanyi never suited up for the Marauders’ boys’ basketball team, it was there that he was discovered by a coach named Keith Odister, who convinced him to join his AAU team, the Nor Cal Pharaohs.

That connection jumpstarted Ifeanyi’s growth into a bona fide prospect. He struggled through the spring and summer of 2005 with the Pharaohs, but got to play through his mistakes. In addition, he worked with Guss Armstead, a skills trainer who worked with future pros from all over the Sacramento area.

In the fall of 2005, he continued his hoops education as a part-time student at Yuba College, where he took actual classes in basketball. The coach there, Doug Cornelius, worked with Festus on his skills before and after class, and eventually convinced the 6’8” 16-year-old to practice with the team and help out as the videographer.

“I'm fumbling the ball all over the place,” Festus says, “but I'm learning as I'm failing.”

By the time he returned to the travel-ball scene in the summer of 2006, Festus did more than look the part of a player. He became, as he calls it, “Bigfoot in the AAU circuit.” College coaches from across the country wondered where he’d come from and how he’d flown under their respective radars.

That summer, Festus cemented his love for the game at the Las Vegas Big Time Tournament, where he not only logged his first in-game dunk, but also did so with defenders draped all over his shoulders.

Oh my God, that felt amazing, he thought. I can do this in traffic? With people around me? Wait. What?

College coaches took notice, and the scholarship offers came in droves. In the fall of 2007, after his mother and siblings emigrated from Nigeria while his father stayed home to run his beer distribution business, Festus enrolled at Vanderbilt University on a basketball scholarship. He had heard from hoops powerhouses like Connecticut and Florida, but felt the best path to a future in medicine ran through Nashville.

He redshirted as a freshman, so he could work on his game and get ahead of his coursework in biology, and came off the bench for two seasons behind an aspiring pro from Australia named A.J. Ogilvy. Over those years, Festus’ frame and game grew, to the point where A.J. couldn’t score over his 6’11”, 260-pound defender in practice.

Along the way, Festus fought through injuries and improved on the court to the extent that a career in basketball became a distinct possibility. Over his final two collegiate seasons, he averaged 11.7 points, 6.1 rebounds and 2.3 blocks while helping the Commodores extend their streak of NCAA tournament appearances to three under then-head coach Kevin Stallings.

To aid his shift towards hoops, Festus switched his course of study from the rigors of biology to economics, with a schedule that fit more cleanly with his athletic commitments. Shortly after graduation, he became the last pick of the first round (No. 30) by the Warriors in the 2012 NBA draft—in the same class that saw Harrison Barnes and Draymond Green head to Golden State.

Three years later, after more battles with his body, Festus became an NBA champion with the Warriors. He and his teammates, including All-Stars Stephen Curry and Klay Thompson, nearly went back-to-back in 2016, before LeBron James, Kyrie Irving and Kevin Love led the Cleveland Cavaliers to an historic comeback from a 3-1 deficit in the Finals.

Throughout that journey, Festus found ways to give back. At Vanderbilt, he participated in community service projects around Nashville, and assisted residents when a flood hit the city in the spring of 2010. In Golden State, he started hosting Thanksgiving and Christmas meals for families in need. Even though he hasn’t played in the NBA since the 2016 Finals—he signed a two-year deal with the Portland Trail Blazers that summer, but never appeared in a game due to persistent knee problems—he’s not only kept up those holiday traditions, but also added volunteer work in Sacramento while living with his family and rehabbing in nearby Elk Grove.

“I grew up knowing that you're given so you can give, right?” he says. “I don't just take.”

Festus had accomplished more than enough to justify a triumphant return to Nigeria. He’d graduated from a prestigious university, become a first-round NBA draft pick, lifted the Larry O’Brien Trophy, made millions of dollars from a sport he picked up at the age of 15, and extended a helping hand to the communities in which he competed.

But timing a trip home was always a challenge. Going back for Christmas wasn’t an option, since that landed right in the middle of basketball season. Summer trips to Africa were tricky, too, since he was usually busy either working on his game during an offseason shortened by a long playoff run or recovering from an injury.

And though Festus hadn’t played in the NBA since 2016, that didn’t mean he was free to roam over that time. The knee injury that kept him out of the league had necessitated multiple procedures—including one in which doctors at The Steadman Clinic in Colorado transferred cartilage from a cadaver—that led to a slow, arduous rehab.

Festus did his best to embrace his circumstances. He turned his recovery process into a social media movement, inviting his fans to follow along as he worked towards “Rebuilding the Beast.”

But with his basketball career on the line and his body in a fragile state, Festus couldn’t risk a long journey to Nigeria, let alone take an extended break from his rehab program. He could keep up with his cousins through WhatsApp, but had to decline yearly invitations to coach at camps back home while his knee remained in limbo.

That is, until 2019.

Early in the year, Festus finally started working out on the court again. His return to normalcy remained slow, but at least he could get around. No longer would mobility limit his desire to reconnect with his roots. If anything, going back to Nigeria would serve his personal needs and goals.

“I was really struggling because my rehab was taking a long time,” he says. “I almost needed reinvigoration of some sort because I was getting worn out, getting burnt out.”

There was also a sense of urgency on Festus’ part. He had heard that his 90-year-old grandmother was sick and losing her memory and her eyesight. If he didn’t act soon, he might miss his last chance to see her—and for her to recognize him.

So when Festus got the call from Franck “Bazu” Traore at the NBA’s office in Nigeria this past summer, about participating in the annual “Power Forward” camp in the capital of Abuja, he had to—and could—consider it more seriously.

The timing of the opportunity took on a different meaning in Festus’ mind, too. After 15 years away, he had now spent more of his life in America than Nigeria. That he was set to be sworn in as a U.S. citizen in mid-September only drove home the fortuity of it all.

“The way I envision our lives is that God is writing our books, each one of us, and he licks his pen. He's, like, ‘Man, you won't believe that's about to happen next,’” he says. “That's literally how it happens in my head.”

Despite the cosmic confluence of factors and his own desire to go, Festus heading home was no slam dunk. He had to check with his physical therapist to make sure he would be fine to travel overseas on his knee. He had to huddle with his parents about security, especially given the state of unrest in Nigeria, with terror groups like Boko Haram instilling fear and inflicting violence at large. And he had to check his own gut, to make sure he was fully committed.

“Whenever a decision is back and forth, my trick is, I go to sleep, I think about the decision,” Festus says. “I go to sleep and I wake up. And when I wake up, however I feel about that decision is what I'm going with.”

So Festus slept on it. When he woke up the next day, he called Bazu with good news.

“They sent me the document to sign that I was going to be a part of the camp, and that was all she wrote,” he says. “I was really excited about it.”

Despite concerns about health and safety, Festus Ezeli went to Nigeria for the NBA's "Power Forward" camp this past summer. (Courtesy of Festus Ezeli)

As Festus boarded the flight for his trip from California to Nigeria, that excitement turned to nerves. He wasn’t so much worried about the 21-hour journey ahead of him as by what it would be like when he landed. He had envisioned that moment and all that would follow, over and over again, for 15 years.

The food, what does it taste like over there as opposed to the food over here?

My family, what do they look like?

What are they gonna think about me and my height and what I look like now, as opposed to how I used to be?

Are we still gonna be as close and are we still gonna have the camaraderie?

“There was so much going through my mind,” he says, “but once I landed and I touched down and that warm air hit me, I was, like, ‘Man, I'm really home, I'm really here.’

“I just couldn't believe it. I almost kept pinching myself, just to make sure this is real.”

Festus touched down at Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport in Abuja around 11:30 p.m. local time on the final Tuesday of September. His dad was there to greet him, as were members of the NBA’s security detail. Together, they whisked him away to the Transcorp Hilton Abuja, where he was scheduled to spend Wednesday getting acclimated and recovering from jet lag.

Except, there was no jet lag. Festus awoke that next day feeling refreshed. It was as if his mind and body had been preparing for this moment, to ensure that he could maximize his time in Nigeria whenever he returned.

Festus didn’t venture far from his hotel during that first day back. He kept up his rehab program at the gym and in the pool at the hotel before hitting the buffet for a taste—or, really, a feast—of home. Before him lay a spread of epic proportions, from akara (fried bean cakes) and akamu (corn porridge) to efo riro (spinach stew), boiled yam, salads and puff puff (deep-friend dough). By and large, the flavors and textures were familiar, but Festus hadn’t experienced them with this degree of freshness and authenticity since he was a teenager.

“My mom does a great job over here in America of cooking our food, right? So we have family members that fly over here and they give her ingredients, and she cooks a lot of different Nigerian food. So I've never lost my palette for it,” he says. “But there's still something about food that's back home, there's still some things that she can't get over here." One was ogiri, a flavoring made of fermented seeds.

A glimpse of the buffet at Festus' hotel in Abuja. (Courtesy of Festus Ezeli)

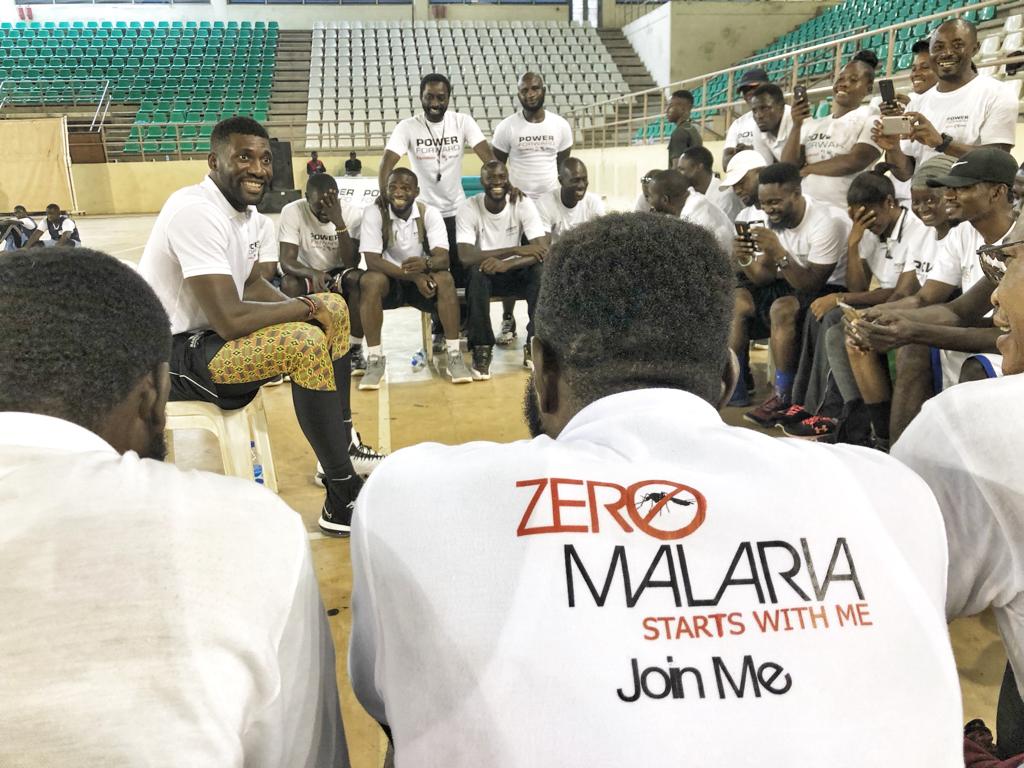

Come Thursday, Festus was on his feet at the Power Forward camp. For the better part of three days at Moshood Abiola National Stadium in Abuja, with temperatures hovering in the mid-80s, he was busy coaching, cheering on and lending words of wisdom to as many of the 3,000 boys and girls there as he could.

On the last day of the month-long camp, Festus watched as the attendees competed in the championship and third-place games. He was struck by the sheer emotion and passion on display—how ecstatic were the victors and how sullen were the losers.

“The kids [on the losing team] were crying. You know, it was a serious thing for them because they took this that seriously,” he says. “I was so inspired by that. But I didn't want that moment to pass without actually instilling something in them.”

So Festus gathered the losing team together to share a lesson from his own life that transcended wins and losses.

“I know this thing hurts and it sucks. I'm so excited that you guys wanted to win that bad, you guys are this competitive,” he told them. “But I don't want you to waste your pain. I don't want it to end here. The fact that you're crying, yeah, I've lost so many games in my career that you wouldn't even believe. But I've also won so many that the wins are way more than the losses.

“You don't cry to stop; you cry to keep going. Don't get frustrated by the fact that you didn't win. Be better. Grow through it, don't just go through it.”

The kids hung on every word, their eyes drying, their frowns slowly turning to smiles. In truth, everyone Festus spoke to at the camp was just as attentive. There, in the flesh, was an NBA player—one who was born and raised in Nigeria—right in front of them. How often does that happen?

They were excited to take everything they could from Festus—and not just his thoughts and words. They scrambled for selfies, sought shout-outs to his basketball friends back in the States—even clamored for the bands he had around his powerful wrists. Festus, in turn, was happy to oblige.

“I gave one as a gift to a kid, and they were all so excited that they all wanted one,” he recalls. “So they took all the wristbands off my wrist, which is cool. I was excited about that. I wanted them to have my stuff.”

After his first day at the camp, Festus and his dad went to a local market to restock on wristbands, both for himself and his brothers back in California.

The next day, the kids took all of his wristbands again. So he went back to the market to get more. Third day, same story.

“They just asked for them and I'd give them because it's about the kids,” Festus says. “I'm there for them and I want them to enjoy, and I want to leave an impression on these kids, so they know how to treat other people when they're in the same position.”

That last day, a 13-year-old named Atiku came up to Festus, seeking not a wristband, but a game of 1-on-1. Atiku wasn’t particularly big or strong for his age. Nor was he dressed for competition in slacks and dress shoes.

Still, Festus wanted to help this courageous boy, though he first had to give his time to interviews and other end-of-camp obligations.

“If you wait and I get done talking to everybody,” Festus told him, “we can play.”

So Atiku waited, and waited, and waited some more. After about an hour, Festus finished and Atiku was still there.

“Let’s go,” Festus told him.

As Festus recalls, he deferred the opening possession to Atiku. The kid made a move to get to the rack, only to find Festus hovering over him. Without a live dribble or a clean view of the hoop, Atiku was stuck.

Rather than surrender, he spun into an open space and tossed the ball up behind his head. It didn’t go in, but Festus admired the kid’s gumption.

“I want to see it again,” he told Atiku.

So Festus gave him the ball back. Another dribble move. Another shot. Another miss.

Atiku was upset with the result, so Festus gave him a third try. Same result. More disappointment for Atiku.

“Yo, be easy with yourself,” Festus told him. “You're in your school uniform.”

“Yeah, but no,” Atiku replied. “I know I should be better.”

“Listen,” Festus said, “I'll be back here next year, and I want you to be better than you were today. I want this to be motivation for you.”

After a bit more pep talk, Atiku thanked Festus and left.

“My heart is full after that,” Festus says.

As Festus was saying his goodbyes, one of the coaches came up to him.

“This kid wants to talk with you,” the coach said.

It was Atiku again.

“I don't really have the words to say,” he began, before finding the words he sought. “I just want to say thank you for you being here and giving to all us kids. Because you could've just came and sat and maybe said a couple words, but you were out here with us. You're sweating, you're jumping around, you're playing 1-on-1, you're out here jumping having fun with us, you're dancing with us.

“That's really cool. You're an inspiration to me.”

Then, Atiku handed him a gift: a Fan Milk vanilla-flavored ice cream bar in its wrapper, the kind Festus used to eat when he was a kid growing up in Nigeria. The package featured prideful phrases in Nigerian Pidgin English.

Naija For Life, meaning “Nigerian for life.”

This Naija Na We Own, which translates to “Nigeria is ours.”

I follow rep Naija, or “I represent Nigeria.”

The Fan Milk treat that Atiku gave to Festus. (Courtesy of Festus Ezeli)

Then, Atiku tried to hand Festus some money—the equivalent of about 14 cents U.S.—prompting Festus to ask, “What is the symbolism of you giving me all this?”

“Well,” Atiku replied, “you gave us a lot and I just want to give something back.”

Atiku wasn’t the only one who felt that way. Just as Festus was ready to leave, he felt a tug on his shirt. It was a young girl, no older than 13.

“Hey,” she said, “I have something for you. I saw everybody took your bands.”

She slipped a band of her own, in the green and white of Nigeria’s flag, onto Festus’ wrist and said, “Thank you so much.”

“That spirit right there is the African spirit,” Festus says. “And so when I said I came home, I came home and it reminded me of where I came from. It reminded me of the things that made me who I am, and the things that inspire and motivate me to be a good person, because these kids are watching me.”

As much as the Power Forward campers filled Festus’ heart, his trip wasn’t over. He still had a family reunion to attend on Sunday in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city.

But first, he and his father were off to Benin City, Festus’ hometown, albeit only for a connecting flight. There wasn’t time for a full stroll down Memory Lane, or even for Festus to get a tour of his family’s new house in town. The layover on Saturday afforded him about an hour to ride around and take in what little he could of Benin City through the window of a taxi.

After that brief stop, Festus and his father were on another plane, off to Lagos. They got in too late to visit with anyone, so they opted to go straight to the hotel, to rest up for the family-filled finale of Festus’ big trip.

“So Sunday morning comes up and I feel like my dad is messing with me,” Festus says, “because I woke up and I’m like, ‘Yo, come on, let's go!’ And he's like, ‘Well, you know, we have to wait on your cousin and all these others things.’”

Eventually, Festus’ cousins arrived at the hotel. They ate together and hung out, catching up in between bites of Eba, pounded yam, fufu, jollof and an assortment of other rice dishes and soups.

Then, it was off to see Mercy, Festus’ grandmother. Though she wasn’t awake for long, he saw in her a reflection of himself—the energetic boy he’d been and the adventurous man he’d become, linked across years and miles by the same inner spirit.

“I always felt like I got it from my grandma,” he says. “I was always very similar to her in that regard because she was always rambunctious, kind of jumping all over the place and traveling and meeting people and social.”

At 90, all but stuck in her bed, she was no longer that person.

“I feel like I missed a lot of that time with her, where I could've asked so much, we could've done so much together,” Festus says. “It was such a bittersweet moment for me, and I was so happy to be there with her.”

So much had changed in the half a lifetime Festus had been away (“First of all, everybody was shorter than I remember,” he quips). Yet, despite those years apart, through all the championships won and couples wedded and kids born and raised, he and his family—in this case, about 20 aunts, uncles and cousins—seemed to snap back into place.

“You would think that it would all just kind of fall apart,” he says. “But it was almost like, ‘Oh my God, dude, let me tell you about all the crazy stuff that's happened to me over the last 15 years.’ Almost like, I went away for a couple days and came back just to tell them.”

Festus and his family reminisced about the old days. His cousins shared stories about all the trouble he caused as a kid—which (he claims) he didn’t remember. After some hearty goodbyes, Festus headed back to the airport with plenty to contemplate during his long journey back to the U.S.

“It made me so happy because I felt like I didn't lose that,” Festus says, “because sometimes, as time goes on, people just move on and forget each other, but I was so happy that my family was still intact.”

Festus spent the final day of his trip to Nigeria with family in Lagos. (Courtesy of Festus Ezeli)

After 15 years in America, Festus returned to Nigeria a changed man, far from the towering teenaged boy who went to live with his uncle in Yuba City. But while six days back home didn’t alter his body, the experience left him re-energized.

“I felt like Superman,” he says.

Festus has attacked his rehab with a renewed fervor and a focus on competing again in the new year. He’s been cleared to play, which means he can get back to playing pickup and, in the process, restore his timing and conditioning. With any luck (and a lot of hard work), he’ll be ready to battle for a spot on Nigeria’s men’s national team in time for the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

“I can see the light,” he says. “I'm excited.”

Beyond his on-court ambitions, Festus came back with ideas about what more he could do to help people in Nigeria, inspired by the collaboration between schools and camps that he saw firsthand at Power Forward. He sees education and providing material assistance to the country’s neediest as the best ways to reduce the radicalization that has gripped Nigeria in recent years.

“There are a lot of beautiful people in Nigeria who are really struggling below the poverty line,” he says, “and that is where the problem starts.”

Festus also returned with a feel for both the potential and the pitfalls facing the Basketball Africa League (BAL), the NBA’s first full-fledged league outside of North America. The BAL is set to launch in March 2020, in a region of the world where soccer still rules and proper basketball facilities remain scarce.

“I think that the infrastructure is what everybody's working on,” he says. “That's exactly what the NBA is doing. I'm super proud of the NBA for going into that market.”

Festus was in Charlotte for the announcement of the BAL at the NBA Africa All-Star Luncheon this past February. He would like to be involved in the league in some way, whether serving as an ambassador for the league or, perhaps, competing in it, health permitting. As just the second native-born Nigerian to win an NBA championship, after Houston Rockets legend Hakeem Olajuwon, he feels as though “it'll only make sense for me" to be involved, he says.

He has connected with other African-born NBA veterans, including Bismack Biyombo, who has dedicated his resources to building schools in the Democratic Republic of Congo; and Al-Farouq Aminu, an American-born Nigerian who’s held basketball camps in West Africa for years. He’s felt more motivated to rejoin their ranks in the league than he had in months.

Because now, he knows who’s behind him. Not just family and friends, but an entire country—and the most populous one in Africa, at that.

“I can't wait to get back on the floor because my grandma is watching me, kids are watching me, my people in Nigeria are supporting me,” Festus says. “The trip was, to say it was well worth it, that would be an understatement. It was above and beyond anything I expected.”

Josh Martin is the Editorial Director of CloseUp360. He previously covered the NBA for Bleacher Report and USA Today Sports Media Group, and has written for Yahoo! Sports and Complex. He is also the co-host of the Hollywood Hoops podcast. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Instagram

Twitter

Error: Could not authenticate you.

Facebook

Subscribe